Finding Dad in a Museum

Browse MoreDescription

There I was, on my Great Hispanic American History Tour, visiting yet one more gallery where our heritage is on display, and much to my surprise — through my camera lens — I made a discovery that almost knocked me down.

I was visiting Miami’s Freedom Tower, the National Historic Landmark that served as the U.S. government’s “Cuban Refugee Center” in the 1960s and early 1970s, and I was determined to write a very personal account of what that building means to me — how it received my own family when it served as “the Ellis Island of the South.”

But nothing had prepared me for the shock I received last week when I entered the tower — now a museum — for the first time in more than 50 years.

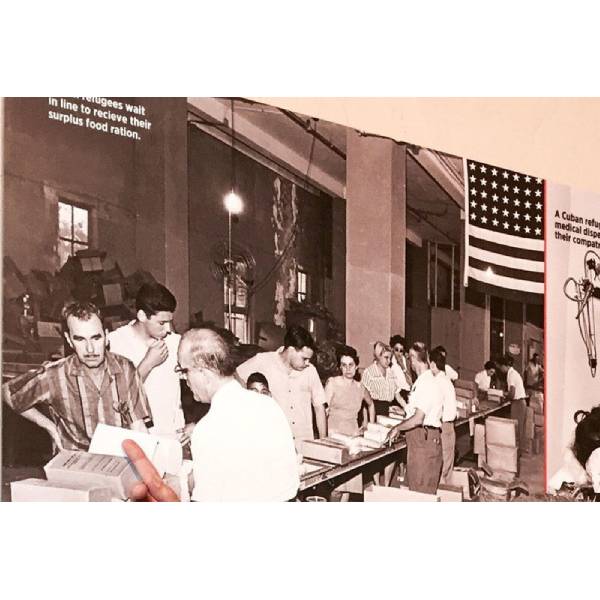

As I viewed a wonderful photo exhibit depicting what occurred there in the 1960s, I was already overwhelmed with nostalgic emotions. The exhibit, “The Exile Experience: Journey to Freedom,” shows the crowded waiting rooms filled with refugees and the social workers trying to assist them, the doctors and dentists treating children, the refugees receiving surplus food rations and used clothing, and families applying for relocation assistance and planning to move to other parts of the country.

It shows the faces of desperation of a people who had given up everything — just to be free.

“I was part of that history,” I kept telling myself. “The families in those photos could easily be my family.”

And then, as I began to take my own photos of the exhibit, in the forefront of a poster-sized photograph, I spotted my own father.

My knees buckled. My eyes instantly watered. And my mouth uncontrollably uttered the words, “Oh, God! Oh, God! Oh, God!” I took several steps backward and nearly lost my balance. For a moment, I didn’t know where to put myself. I thought I was going to faint, so I felt this urge to sit on the floor, but somehow I managed to resist it.

Staring at that photo is what held me up. I was mesmerized. It shows my father, Benito Perez, at the age of 42, about to receive the family’s monthly food ration at the Freedom Tower in 1962.

I had visited his gravesite a couple of days earlier. He was 67 when he died of cancer in 1987.

I felt immense joy and sadness at the same time. I have seen many wonderful and impactful exhibits during the past few years, but none has been so shocking and personal. None had made me cry tears of joy.

Before long, other museum visitors were offering to take my picture next to my father, and I was posing next to him — bursting with pride.

And shortly after that, a museum administrator wanted to know all about my father and my family history. I went there hoping to interview museum officials, and they ended up interviewing me.

“Tell me about your father,” said Sierra Manno, the museum’s front desk associate. “We like to tell anecdotes about the people in the photos when we give our tours.”

In my cross-country search for our hidden Hispanic heritage, I have been on many of those anecdote-animated museum tours, but I never imagined that my own family history could be part of one.

As I walked through the corridors of the Freedom Tower, I kept seeing myself as the 11-year-old boy who took his first step to freedom in that building shortly after arriving from Cuba on April 7, 1962.

“In the 1960s, as the Freedom Flights continued to bring two plane-loads of Cubans daily to Miami, the Freedom Tower expanded and converted,” the exhibit explains. “The second floor was the processing center, the basement became the medical and dental clinic, the third and fourth floors were records centers.”

It was there that my refugee papers were processed. It was there that I crossed my golden gate to a new life in the United States — for which I will be eternally grateful.

“El Refugio” — that’s what we called it in Spanish. That’s where I was treated by dentists and other doctors and where I acquired my first winter clothing and my nerdiest eyeglasses. That’s where, once a month, my father would pick up a Red Cross care package, containing powdered milk, peanut butter, lard, canned meat and a block of American cheese. That’s where he constantly resisted the temptation to have our family relocated to another state.

“Cubans leaving for the U.S. only carried three sets of clothing — and no cash or valuables. Once they left for the U.S., their homes were confiscated by the communist government,” the exhibit explains. “Refugees relocating to a cold climate were given donated coats and shoes. They also received financial assistance, from $25 to $60-a-month ($155-$460 in today’s economy) depending on the size of the family. Once they found employment and could support themselves, the aid stopped.”

My parents almost took up offers to move to Arkansas and Texas, but we managed to survive in Miami, thanks to my father’s business ingenuity. He bought an old station wagon and created his own business by buying fresh produce from the farmers market and reselling it to Little Havana’s Cuban bodegas. A proud man, he took our family off public assistance as rapidly as he could. Eventually, the business grew into a van, and his bodega clients became supermarkets. And that was the business that sustained our family until he died in 1987.

As his Saturday assistant, I spent my teenage years carrying sacks of onions and potatoes — and learning to appreciate how hard my father worked during the rest of the week. I saw all the sacrifices he made, leaving behind a comfortable life in Cuba so that my brother and I could live in a free society.

Only 13 years later, in 1975, that 11-year-old boy had become the Miami Herald reporter assigned to write an in-depth story on the history of the Cuban Refugee Program and the U.S. government’s plans to phase it out gradually. Though the Cuban Refugee Center at the Freedom Tower was closed in 1974, the Cuban Refugee Program continued several years longer, and it was my job to chronicle its history and forecast its demise.

At that time, I reported that of the 650,000 Cubans who had immigrated to the United States since Fidel Castro took power in 1959, some 460,000 had sought U.S. government assistance. The federal government had spent more than $1 billion to help the exiles find jobs, give them career training, provide for their medical care, give them financial assistance and help them relocate from Miami to other parts of the country. Almost 300,000 had resettled in all 50 states.

In the spring of 1975, shortly after the Cuban Refugee Center was relocated to smaller offices in Little Havana, the program’s acting director, Philip A. Holman, told a congressional committee that 8 in 10 Cubans were able to stand on their own feet and introduced a plan to gradually discontinue the program.

“The basis for this (phaseout) proposal continues to be that the emergency situation which gave rise to the Cuban refugee program over 14 years ago has passed,” Holman testified, “that very few new Cuban refugees are reaching the United States and that the refugees, as a group, have moved into the economic stream of American life, paying federal, state and local taxes on the same basis as other residents of the communities in which they live.”

Though the program was phased out during the next few years, the Freedom Tower changed hands for the next 20 years, until 1997, when it was purchased for $4 million by the late Cuban exile leader Jorge Mas Canosa, who died before realizing his dream of turning the whole building into a Cuban exile museum.

The Mas family eventually sold the tower to developer Peter Martin, who donated it to Miami Dade College in 2005. The Mediterranean Revival-style tower and its museum are now part of the college campus, facing Biscayne Boulevard in downtown Miami and striking an amazing contrast with the surrounding modern high-rises and the futuristic area where the Miami Heat play basketball.

The building opened in 1925 as the home of the Miami Daily News. It was designed by the same architects who built some of the country’s most renowned hotels, including the Biltmore in Coral Gables, Florida, The Breakers in Palm Beach, Florida, and the Waldorf Astoria in New York City. But it was modeled after a bell tower in Spain, Seville Cathedral’s Giralda.

“The Miami Daily News moved out of the tower in 1957. In the summer of 1962, the U.S. federal government leased the building, which was large enough to process the high number of Cuban refugees fleeing Fidel Castro’s communist regime,” the exhibit explains. “El Refugio became the Ellis Island of the Cuban exodus. It was a one-stop center for the refugees to obtain healthcare, housing, financial assistance and education. The Freedom Tower is the single most important physical manifestation of this period of Cold War-era politics. To this day it remains an iconic symbol for Miami’s Cuban exile community.”

For me and my family, now that I’ve found my father in one of its exhibits, the Freedom Tower is even more significant than I imagined. And that precious moment when I spotted my father through my camera lens will live with me forever. My Great Hispanic American History Tour has brought me home.

To find out more about Miguel Perez and read features by other Creators Syndicate writers and cartoonists, visit the Creators Syndicate Web page at www.creators.com.

Reviews

There are no reviews yet.